|

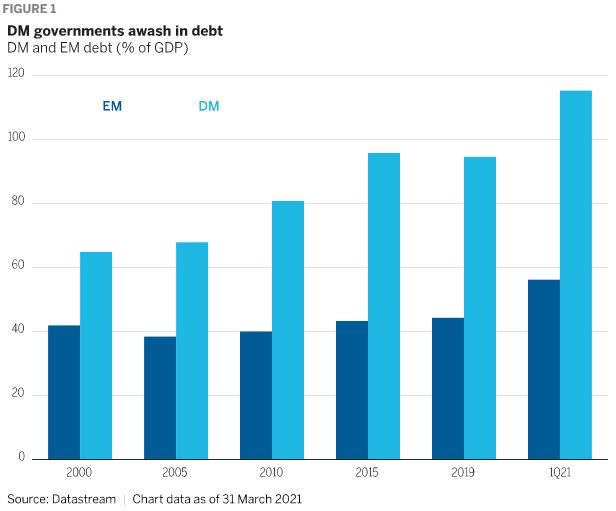

At a high level, it’s fair to say that economic and other fundamentals in developed markets (DMs) have become increasingly fragile over the past decade-plus. During that period, severe stress episodes like the global financial crisis (GFC) and the COVID-19 pandemic have spotlighted and, in some cases, accelerated this weakening of fundamentals in some countries. Fragile DM Fundamentals For starters, many DM governments currently find themselves awash in debt. A variety of financial and political strains since the 2008 GFC has resulted in an unprecedented surge in government debt burdens. In fact, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), aggregate DM debt has been climbing steadily since all the way back to the turn of the millennium, outpacing the rate at which EM debt has risen over the same period (Figure 1). Long term, we see DM debt continuing to rise as social fissures, including income inequality, intensify political pressures to expand the social safety net in support of less fortunate citizens. |

|

|

|

On the monetary policy side, global central banks have repeatedly come to the rescue in times of crisis. As a percentage of GDP, DM central bank balance sheets have been growing since 2008, ballooning most recently in the spring of 2020 in response to COVID-19. Relatively tame inflation for the better part of the past decade has made it easier for central banks to pursue and maintain accommodative policy, including historically low interest rates. In addition to financial stressors, the quality of government institutions worldwide appears to have deteriorated. The Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index recently showed that the world is in the midst of a “governance recession” based on five key categories across a range of global governments: 1) electoral process and pluralism; 2) civil liberties; 3) the functioning of government; 4) political participation; and 5) political culture. A key takeaway here is that minority and lower-income populations in some countries feel “disenfranchised.” This is worrisome because stronger government institutional quality and greater income equality tend to breed higher GDP per capita — a trait often associated with some DMs — as well as lower volatility in the form of a more predictable business operating environment. It is noteworthy that the US and the UK, two of the world’s “most developed” markets, both seem to be moving in the wrong direction on this front. Thus far, investors have given DMs a “pass” on these issues due to an entrenched belief in DMs’ continued policy flexibility and institutional strength. Indeed, markets haven’t seemed to really care about mounting government debt loads and balance sheets except during very challenging periods like the eurozone debt crisis, Brexit turmoil, and COVID-19. (On all three occasions, European investment-grade corporate bond spreads spiked sharply.) To us, this lack of any sustained adverse investment fallout suggests that global markets remain largely oblivious to, or at least complacent about, the fragile state of fundamentals in many DMs. Historically, complacent markets are often a recipe for trouble. Possible paths, investment implicationsThat complacency could be shaken going forward if DM fundamentals were to further erode and become more difficult to overlook, or if some DMs were to exhibit more “EM-like” behavior (Figure 2) that began to test investors’ faith in their degree of policy flexibility. (As one recent example, UK markets acted decidedly more “EM-like” following the pivotal 2016 Brexit vote.) This would be approaching a worst-case outcome, but one that cannot necessarily be ruled out. |

|

|

|

Under this type of negative scenario, markets could start to mete out harsher punishment to some DM assets over time. While not a complete list, potential investment implications include (Figure 3): Credit markets

Equity markets

Of course, there is more than one possible path to consider regarding the future evolution of DMs. The “EM-ification” of DMs is not an irreversible trend if appropriate measures are taken to slow or unwind it. For instance, along with the negative outcome described above, there is a potential positive scenario whereby DM governments ratchet up their level of fiscal spending, strategically investing in areas like infrastructure and “green” energy. Such targeted investments could have a meaningful long-term impact in terms of boosting a nation’s productivity, economic growth, and policy flexibility. Potential investment implications of this scenario include (Figure 3): Credit markets

Equity markets

|

|

|

There is also a potential “status-quo” scenario where DM government debt keeps rising, but policy flexibility persists, and interest rates stay relatively low. Bringing it all together

|

About the Author:  Nanette Abuhoff Jacobson is Managing Director, Global Investment Strategist, and Multi-Asset Strategist for Wellington Management. As a global investment strategist, she shares her views on market trends and opportunities with subadvisory clients as well as their sales organizations and major broker-dealers and distributors. As a multi-asset strategist, Jacobson consults with clients on strategic portfolio issues and works with investment teams across the firm to develop relevant investment solutions. Prior to her current role, she was the director of Fixed Income Product Management, where Jacobson was responsible for ensuring the integrity of the firm’s US and global fixed income approaches and driving business success in terms of business strategy, new product development, and retention of existing clients. She also played a key leadership role in deepening the firm’s reputation as a fixed income thought leader globally. Jacobson joined Wellington Management in 2005 as a fixed income investment director for US fixed income products. Before joining the firm in 2005, she was a managing director at JPMorgan in the Investment Bank. Jacobson was an investor client manager for pension funds in North America (2003 – 2005) and was the senior US fixed income strategist (1989 – 2003). She also worked in the Financial Strategies Group at Security Pacific National Bank, where she developed software to value complex financial instruments (1986 – 1989) after working as a programmer for Interactive Data Corporation and IBM (1983 – 1986). Jacobson received her bachelor's degree in computer science from Barnard College, Columbia University. Disclaimer: Nanette Abuhoff Jacobson is Managing Director, Global Investment Strategist, and Multi-Asset Strategist for Wellington Management. As a global investment strategist, she shares her views on market trends and opportunities with subadvisory clients as well as their sales organizations and major broker-dealers and distributors. As a multi-asset strategist, Jacobson consults with clients on strategic portfolio issues and works with investment teams across the firm to develop relevant investment solutions. Prior to her current role, she was the director of Fixed Income Product Management, where Jacobson was responsible for ensuring the integrity of the firm’s US and global fixed income approaches and driving business success in terms of business strategy, new product development, and retention of existing clients. She also played a key leadership role in deepening the firm’s reputation as a fixed income thought leader globally. Jacobson joined Wellington Management in 2005 as a fixed income investment director for US fixed income products. Before joining the firm in 2005, she was a managing director at JPMorgan in the Investment Bank. Jacobson was an investor client manager for pension funds in North America (2003 – 2005) and was the senior US fixed income strategist (1989 – 2003). She also worked in the Financial Strategies Group at Security Pacific National Bank, where she developed software to value complex financial instruments (1986 – 1989) after working as a programmer for Interactive Data Corporation and IBM (1983 – 1986). Jacobson received her bachelor's degree in computer science from Barnard College, Columbia University. Disclaimer:

The views expressed are those of the author at the time of writing. Other teams may hold different views and make different investment decisions. The value of your investment may become worth more or less than at the time of original investment. While any third-party data used is considered reliable, its accuracy is not guaranteed. For professional, institutional, or accredited investors only. Wellington Management is an Associate member of TEXPERS. Follow TEXPERS on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn as well as visit our website for the latest news about Texas' public pension industry. |

Oct

27

Share this post: